Scottish Government Knew Its Consultation Platform Would Restrict Public Objections

- Home

- Scottish Government Knew Its Consultation Platform Would Restrict Public Objections

- 25 January 2026

- 14 Comments

Article update: 26 January 2026

This article has been updated to reflect additional wording added to the Energy Consents Unit portal.

A fixed technical ceiling incompatible with statutory consultation duties

The Scottish Government adopted the Energy Consents Unit online consultation platform knowing, or having reason to know, that it imposed a fixed limit on the length of public representations.

That limit is precisely 32,700 characters.

From a technical standpoint, the boundary reflects a server-side character limit applied during the processing and storage of submitted text. It does not arise from user-interface design or guidance, but from how the platform validates and handles representations at the server level.

Crucially, removing or materially increasing this limit would require changes to server-side validation, data handling, and storage arrangements, together with testing and redeployment.

Why the existence of the limit was foreseeable

A hard failure at a precise character count is not subtle. It would have been immediately apparent during development and testing. A system that enforces a strict boundary at exactly 32,700 characters will do so consistently and predictably.

On that basis, it is reasonable to conclude that the limitation was known or ought to have been known before the platform was relied upon as the primary route for public participation. The restriction did not arise through unforeseen use. It was inherent to the system.

This point matters because statutory consultation mechanisms are required to be fit for purpose at the point they are made mandatory.

Why this creates a legal problem

Public participation in environmental decision-making is governed by binding legal obligations.

Article 6 of the Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters requires that public participation be “early and effective” and “meaningful”. These obligations apply to decisions on projects with significant environmental effects and are reflected in domestic law.

Under the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2017, the public must be given a real and proportionate opportunity to comment on Environmental Impact Assessments. The scale and complexity of modern energy developments make detailed representations a practical necessity, not an optional extra.

In addition, long-established common law principles of procedural fairness require that consultation processes be fair in substance, not merely available in form.

A consultation platform that cannot physically accept detailed representations beyond a fixed length is incapable of meeting these standards, regardless of how accessible it may appear.

Why the withdrawal of email submissions is central

Email submissions did not impose any equivalent restriction on the length or structure of public representations. They allowed campaign groups, community organisations, and individuals to submit comprehensive objection documents addressing complex applications.

The decision to withdraw email submissions while relying on a platform known to impose a fixed ceiling transformed a technical limitation into a mandatory constraint on public participation.

At that point, members of the public were no longer choosing to use a limited system. They were required to do so.

This sequence of decisions is significant. Once an unrestricted submission route is removed, the limitations of the replacement system are no longer theoretical. They become determinative.

Why this is not a matter of implementation detail

The ECU platform was not originally designed to function as the sole mechanism for submitting long-form public representations on complex infrastructure projects. Its architecture reflects that.

Attempts to adapt or retrofit the system through interface changes or policy guidance cannot address a server-side character limit that is enforced within the platform as currently deployed. The restriction arises from how text input is validated and processed on the server, rather than from any user-facing design choice.

For that reason, the limitation cannot be resolved quickly or informally. Addressing it would require substantive changes to the system’s server-side handling of representations, rather than incremental adjustments.

What this establishes

The Scottish Government proceeded with a consultation platform that imposed a fixed and enforced limit on public representations, then removed the only digital submission route that did not.

Given the legal framework governing public participation, that decision raises serious questions about whether the current consultation arrangements are capable of meeting statutory and international obligations.

This is not a matter of user behaviour or transitional inconvenience. It is a question of whether the consultation mechanism itself is lawful.

Outdated legal terms and unresolved compliance obligations

Alongside the participation issues, a review of the Energy Consents Unit’s published Terms and Conditions reveals additional concerns about legal compliance and transparency.

The Terms continue to reference the Data Protection Act 1998, legislation that was repealed and replaced by the Data Protection Act 2018 and the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR). This is not a minor drafting oversight. Public bodies are required to ensure that information provided to users about personal data processing is accurate, current, and clear.

Under Article 13 of the UK GDPR, data controllers must provide data subjects with specific information at the point personal data is collected, including the lawful basis for processing, retention periods, and the rights available to individuals. Referencing repealed legislation does not satisfy that obligation.

While additional privacy information may exist elsewhere on the site, the absence of an up-to-date and clearly linked privacy notice within the Terms raises legitimate questions about whether transparency requirements are being fully met.

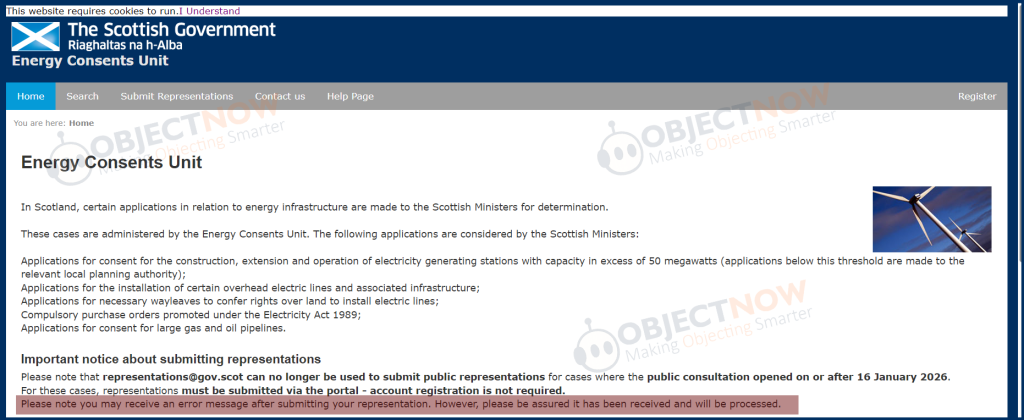

Update 26 January 2026 – 19:33 GMT

Following publication of this article, the Energy Consents Unit quietly updated its website to include a new notice acknowledging that users may receive an error message after submitting a public representation, while asserting that submissions are nevertheless received and processed.

This change was made after concerns were raised by ObjectNow about the operation of the consultation platform and the way it restricts public participation. Notably, the update does not confirm that the system fault has been resolved, nor does it explain how members of the public can independently verify that their representation has been successfully logged when an error occurs.

Despite repeated attempts to raise these issues directly with the Scottish Government by email from campaigners and campaign groups, no response has been provided. The consultation system continues to operate in a known faulty state, with members of the public being told to trust that their submissions have been received even when the platform reports a failure.

This amounts to an acknowledgement of a broken process, not a remedy.

Proceeding with statutory consultations while relying on a system that produces errors, offers no confirmation, and has already been shown to deter or mislead participants raises serious questions about procedural fairness, transparency, and compliance with public participation obligations.

End of update

Cookie and tracking transparency

The Terms page does not adequately explain how cookies or other tracking technologies are used. While the platform does display a cookie banner, it only provides an option to accept cookies and does not allow users to decline non-essential cookies. This falls short of the requirements under the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR), which require users to be properly informed about non-essential cookies and given a genuine choice.

Where a public consultation platform requires the submission of personal data as part of a statutory process, compliance with PECR and UK GDPR transparency obligations is mandatory. Users must be given clear, accessible explanations of what cookies and tracking technologies are in use, what each one does, and how they affect personal data.

This lack of transparency and meaningful user choice compounds wider concerns about the platform’s legal robustness and readiness for use in a statutory public consultation context.

Why data protection compliance matters here

These data protection issues cannot be viewed in isolation. The Scottish Government is requiring members of the public to use the ECU platform as the primary route for participating in statutory consultation digitally. That creates a heightened duty to ensure the platform meets all applicable legal standards.

Where a system both restricts the substance of public participation and operates under outdated or unclear data protection documentation, the combined effect is significant. It undermines confidence in the process and raises questions about whether legal obligations have been fully considered in the design and deployment of the platform.

Why “testing” does not address these issues

Any suggestion that the issues identified arise from testing or transitional arrangements does not resolve the underlying legal position.

Testing is an internal process that must be completed before a system replaces an existing lawful mechanism. It cannot be relied upon to justify ongoing non-compliance once the system has been made mandatory for public use.

If the ECU platform was still being refined or tested when email submissions were withdrawn, that would only reinforce the concern that a lawful participation route was removed prematurely.

Either way, references to testing do not alter the fact that the platform, as currently deployed, carries known structural limitations and unresolved legal questions.

The cumulative effect

When considered together, the issues are not isolated or technical in nature. They reflect a broader problem of readiness and governance.

The Scottish Government adopted a platform that, as deployed, was incapable in practice of accepting detailed public representations, withdrew the only unrestricted submission route, and relied on legal documentation that has not been updated to reflect current data protection law.

Each of these factors would warrant scrutiny on its own. Taken together, they raise serious concerns about whether the consultation process, as currently operated, meets the standards required by law.

When knowledge turns limitation into responsibility

At this stage, the issue can no longer be characterised as a technical oversight or an implementation problem. Once the Scottish Government became aware, or ought reasonably to have been aware, that the ECU platform imposed a fixed and enforced ceiling on public representations, responsibility shifted from system design to governance.

Under the Scottish Ministerial Code, Ministers are accountable to the Scottish Parliament for the policies, decisions, and actions of their departments and agencies. That accountability includes ensuring that statutory consultation processes comply with domestic and international legal obligations.

Where a consultation mechanism is known to restrict public participation in a way that conflicts with those obligations, continuing to rely on that mechanism engages ministerial responsibility.

Why continued reliance is no longer defensible

The critical point is not whether the ECU platform functions as designed, but whether it can lawfully fulfil the role it has been given.

As established, the platform enforces a hard 32,700 character ceiling that cannot be lifted within the existing system through minor changes or guidance alone.

That limitation prevents the submission of detailed objections to complex energy developments and is incompatible with participation duties under the Aarhus Convention, the EIA Regulations 2017, and principles of procedural fairness.

Once email submissions were withdrawn, members of the public were left with no unrestricted digital alternative.

Although postal submissions are permitted, this did not constitute a free or equivalent option. To ensure proof of receipt, any responsible postal submission would require recorded delivery, imposing a financial cost on the sender and creating an evidential burden that does not arise with standard electronic correspondence. In practice, this meant that participation without cost or risk was no longer possible outside the constrained digital system.

At that point, the Scottish Government was no longer offering a genuine choice of submission routes. Instead, it was mandating reliance on a system that was both digitally restrictive and procedurally unequal, while treating paid and risk-bearing postal delivery as a sufficient substitute for unrestricted digital access.

Continuing in that position, with knowledge of the limitation, cannot be defended as inadvertent.

Why “testing” cannot absolve responsibility

Any attempt to frame these issues as the result of ongoing testing does not alter the legal analysis.

Testing is a preparatory activity. It must be completed, and limitations understood, before an existing lawful mechanism for participation is withdrawn. Testing cannot be used retrospectively to justify the removal of an unrestricted submission route or to excuse continued reliance on a constrained system.

If the ECU platform was still subject to testing when email submissions were removed, that decision itself would raise serious concerns about compliance with statutory consultation duties.

Either way, references to testing do not displace responsibility once the platform has been made mandatory.

Why reinstating email submissions is now required

Because the character limit is enforced within the ECU platform as currently configured, the system cannot be brought into compliance in the short term through minor adjustments or guidance alone. Any meaningful increase would require substantive changes to server-side validation, data handling, and storage, together with appropriate testing and redeployment.

In these circumstances, reinstating email submissions represents the only practical measure capable of restoring an unrestricted digital route for public participation. Email submissions do not impose an equivalent character constraint and allow detailed objection documents to be submitted in full.

Continuing to rely solely on the ECU platform without reinstating an unrestricted digital submission route maintains a known and active limitation on participation. That position is not consistent with the legal framework governing environmental decision-making.

Parliamentary accountability

This issue now engages the role of the Scottish Parliament in holding the executive to account.

Ministers are responsible for ensuring that statutory processes operate lawfully. Where a consultation mechanism is known, as deployed, to be incapable in practice of supporting meaningful participation, and no alternative digital route is provided, the matter ceases to be administrative. It becomes constitutional.

If the Scottish Government does not act to restore an unrestricted submission route as a matter of urgency, it will be knowingly maintaining a consultation system that limits public participation by design.

That is not a question of policy preference. It is a question of legality and accountability.

What This Establishes

The evidence establishes a clear sequence:

– A consultation platform was adopted that imposes a fixed and enforced ceiling on public representations.

– That limitation was foreseeable and inherent to the system.

– An unrestricted digital submission route was withdrawn regardless.

– The public was compelled to use a platform that cannot support detailed scrutiny.

– Data protection and transparency documentation has not been kept fully up to date.

Taken together, these factors raise serious and unresolved questions about whether the current consultation arrangements meet the standards required by law.

The remedy is straightforward. Until the ECU platform is substantively reworked to remove the enforced character limit, email submissions must be reinstated. Anything less leaves the Scottish Government knowingly operating a consultation process that restricts public participation in a manner incompatible with statutory and international obligations.

This is now a matter for ministerial action and parliamentary scrutiny.

14 Replies to “Scottish Government Knew Its Consultation Platform Would Restrict Public Objections”

Sadie Clarke

Fantastic work. Well done and thank you for the detective work and determined mindset of your organisation to get all the facts together! And so quickly

ObjectNow

Thank you Sadie.

Frank Armstrong

Well done all involved!! Yet again the SNP Scottish Government is clearly shown to have acted to create an unlawful situation for its own benefit, big energy’s benefit and have by design attempted to hobble the ability of the public to have a voice. This is truly despicable behaviour by an SNP Government which repeated proves it seems to open to corruption!! A public inquiry / Royal Commission must now be called to investigate the conduct of SNP Scottish Government and big energy corporations in the sphere of renewables developments in Scotland. Nothing less will do!! In the meantime all renewables applications must be frozen / halted until such time as the Inquiry / Commission reports.

Heather jardine

It is a disgrace, the way in which this government are trying clearly with this latest infringement to our democracy, to enable the Big Energy multinationals, in their pursuit of wealth, whilst destroying our communities, landscapes and livelihoods, not to mention our health.

Barbara Keane

Well done everyone, an excellent piece of work. Thank you.

Martyn Ayre

Have written to my MSP/Dep FM, Kate Forbes, asking for an explanation/justification. Not holding my breath.

Christine Tait

Well done to all involved in this. I’ve said elsewhere that the Scottish Government always seem to make a pigs ear of anything tech related. I find it astonishing that something so riddled with problems is expected to replace what was a simple and effective way of participating.

Sandra Loder

Thank you for all your hard work on this matter which is so crucial. Words fail me in terms of just how low the depths to which our Scottish Government has sunk. In a digital age where many platforms can easily provide free access for many (although clearly not in this case!) and email is a readily accepted alternative to traditional postal services this is an unbelievably backward step to our democratic rights in this process.

Tina Dawn Marshall

I have put it into the Petitions Committee and will solidify the message when I go to Edinburgh next month.

Nicky Spinks

Thank you for the immense work that you do for communities fighting these applications right across Scotland and for your incredibly quick in depth analysis of the withdrawal of the email response from ECU. I’ve written to South Ayrshire Councillors and MSP’s

Karen Cantell

Absolutely brilliant work. To create an unusable platform and insist on its use smacks of the post office scandal. Our democratically elected members seem to only care about big business and how much money can be made to the total detriment of those people and areas affected.

Anne Brodie

Great work! We will not have our democracy eroded. Just wait till the election. If you want to keep your jobs you’d better be aware of this.

Maureen Beaumont

Very well-researched and detailed comments. Now – how to get this into the public domain and highlight how endemically dictatorial this SG really is. They will stop at nothing to stifle local democracy!

ObjectNow

Author’s note, 26 January 2026:

This article was updated on 26 January 2026 @ 19:33 GMT to reflect new wording added to the Energy Consents Unit portal acknowledging submission errors. A screenshot of the update has been added to the article.